On almost any day in June of 1994, at about 8:00 a.m., if you were to head to downtown Castine from the Maine Maritime Academy–home to the IGMA’s annual Guild School mini camp—you might cut across Deadman’s Alley, turn down the hill on Main, walking past the poet Philip Booth’s white clapboard house, past Town Selectman Paul Manning’s white clapboard house with its driveway full of un-split firewood, past the Post Office, the Castine Inn, the pocket-size McGrath-Dunham Gallery, and on down to the foot of Main, a block up from the town dock, you’d probably find Paul Manning’s rig–an old wooden wheelbarrow full of redeemable bottles and cans–parked in front of the Variety, where you could go in, get a cup of coffee, sit at the community table with Paul, in his yellow Sou-wester looking for all the world like the Gorton’s fishcake fisherman–and find out what’s been going on for the past year. He always introduced us around the table as “the Thomases–they’re from away, but they’re okay.”

After coffee, you might follow Greg Dunham, watercolor artist and new owner of the circa 1885 Ricker—now McGrath-Dunham—building, back up the hill to open the recently refurbished shop. While Greg’s a pretty straight ahead guy, his building is as idiosyncratic as many of the townspeople. The one-story, glass-fronted shop is sandwiched between an alley and a staid, Federal-style building it seems to poke out of the side of like an aberrant gem. A textbook example of vernacular architecture, it doesn’t fit any particular style, but draws from its surroundings, including the slant of the hillside it sits on. In a history-laden town, the Gallery is one of those unsung places where Washington never slept, fought the invaders in front of, nor left a famous tea set. While its history may be unwritten, everyone in town has a story about it.

Among our favorite features of the building is the multi-paned, wiggly-glass bay window with stained glass transoms. Next to that, more glass—an inset 9-paned entry door, with its own transom, and a wood-framed screen door. Capping all is a false-front Mansard roof covered in tiny fish-scale shingles. Inside the walls and ceiling are paneled in whitewashed pressed tin, recently restored floors of wide, unpainted pine planks, and overhead a crawlspace attic. The window box of geraniums, an add-on, and hardly a major architectural element, lends itself to the appeal of the building. Each detail is a facet combining to form a little jewel box of a space, the kind of place that both reflects and magnifies the town’s personality. That summer, it all but jumped into our arms as a great teaching project.

With other projects on the worktable at home taking precedence, it wasn’t until June of 1997 that our students would see our proposal for the following year. Even then we had little idea of the amount of detail required for the project.

With other projects on the worktable at home taking precedence, it wasn’t until June of 1997 that our students would see our proposal for the following year. Even then we had little idea of the amount of detail required for the project.

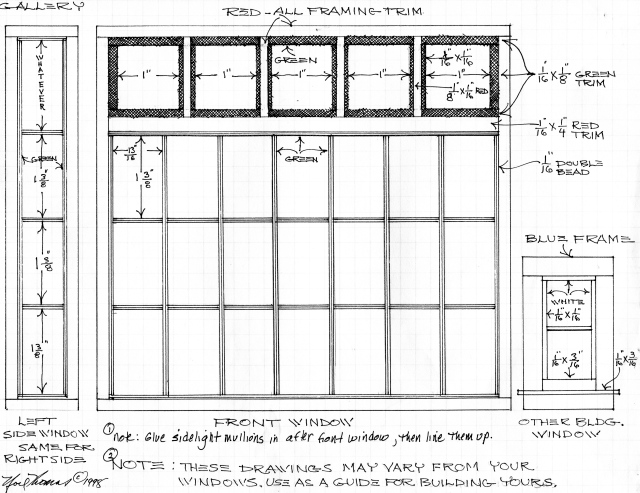

The front window–the building’s crowning glory–made for a lot of mullions and measuring, and measuring was never one of our fortes–we believed in the concept of eyeball geometry, but that eyeball still had to have square corners. The window was made from a single sheet of old glass (with the cut edges darkened with black felt marker to mask the thickness of the glass), framed in cedar channeling. The 1/16th basswood mullions were glued to both sides of the glass, creating the illusion of individual panes. Packing that many sheets of glass to travel cross country unscathed was another challenge. Only one piece broke en route to Maine, which gave us a chance to visit the resourceful Paul Manning (of the yellow Sou-wester), who invited us in and steered us toward his “old glass department” in a kitchen cabinet. Sure enough, we were saved–he had exactly what we needed.

For the false-front Mansard roof, Noel cut 850 cedar shingles (approx. 1/4″ wide) per student, which gave them a good supply of extras for breakage and loss. Cutting that number for the prototype seemed doable, but by the time he was done with ten batches for the 1998 Castine students, more for the 1999 class, plus another 10 for a New Orleans class, he called it quits, and felt lucky to have all fingers intact. We glued the shingles on with Elmer’s white glue–16 rows, 1/4′ apart. Once the glue dried we sanded them lightly, with the grain, to remove burrs, then applied Bug Juice, to darken them, with a 1″ foam brush. Bug Juice can make cedar too dark, so we next applied household bleach, daubed off with a paper towel. From there we experimented with dirty water washes (a lot of water, a dab of Grumbacher acrylic Mars Black, warmed with a smaller daub of raw Umber), and more Bug Juice. It’s just a matter of playing with it to get a nice, weathered look.

In the photo above, you may also notice the leaded stained glass windows, a design we adapted from the original building. Fred Hultberg of Fotocut made the photo-etched brass patterns as a base for the “leading.” In class, to simulate the leading, we applied solder, followed by caming darkener to the top side of the brass designs, then Brass Blacked the backs. The blackened side of each brass piece was then glued to the window glass. When dry, we painted in the color with liquid glass stains. The individual “panes” were then framed with painted stripwood. In retrospect, this process sounds like it could have taken the whole week, but somehow we all managed to work this in with all the other facets of the project.

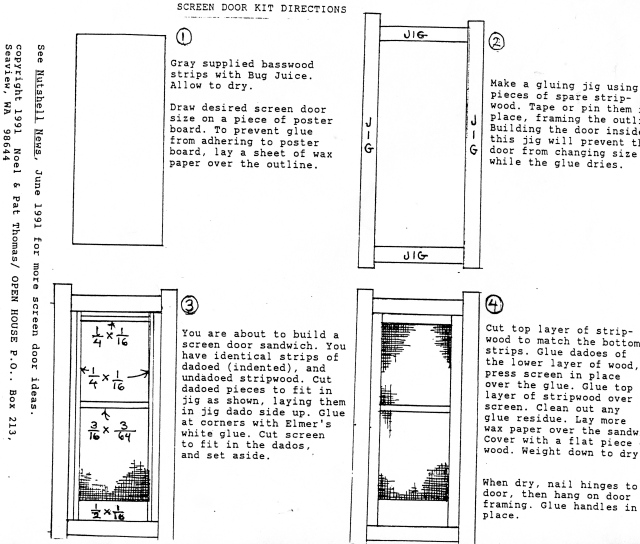

Doors included a front, a back, and, just for fun, a front screen door.

The screening we used was a fine mesh brass sink drainer material we bought years ago from a plumbing supply company in California. To age it we combined wire brushing with applications of Brass Black to the screen. Again, it took time and experimentation to achieve the most reallistic-looking results.

As you can see by the photos above, we chose to age, rather than age and paint the narrow siding. Again, the siding is cut from cedar, which, to save class time, we wire-brushed and Bug Juiced at home. The students glued it on with, yes, more Elmer’s. Then they got to age it with washes. The mossy look at the bottom corner is watered-down Windsor Newton Sap Green watercolor, with real bits of moss glued on. The water meter is a stock miniature item, with various pieces of electrical wiring added. The metal keepers holding it to the building are cut from wine bottle lead, and rusted with burnt sienna tube acrylic.

The photo shows the side of the miniature project attached to a breakaway section of the building next door

And, because we can’t leave anything alone, Noel cut a wider shiplap siding for the cutaway building next door.

Down the open side and around the corner brings us to the back view, showing more of the breakaway building on the left, the Gallery back wall wooden shingle siding, and the alley-side to the right. The kickplate at the bottom of the door was wine-bottled lead aged with caming darkener.

The breakaway side of the building allowed for access to the interior, and gave us a chance to include one of our favorites, an overhead attic crawlspace, borrowing cobwebs from our full-sized basement.

This final side is framed by the interior walls of the building next door, as well as a glimpse of the gallery interior

The prototype interior flooring is cut from 12″ oak planks, because we had bundles of it (so much so that we’re now using the last of it for fireplace kindling). Because this was an exterior only class, the students were free to choose their own floor, along with the rest of the furnishings, once they got home. The cabinet under the window is made from oak veneer covering a 1/4″ plywood base. To replicate the pressed tin ceiling of the original, we used our stock of embossed business cards, acquired in 1980 for our first commercial building, the 2oth Street Emporium.

Then there’s a mystery, another facet of the jewel–along one of the interior walls, Noel attached a large section of mirror, so that when you looked in through the front windows, you saw a reflection of the interior space, making it feel twice the size, and closer in scale to the full-sized building. It was a fake-out, as most people didn’t notice the mirror. It had to have covered the interior left wall, but it has evaded all our photos, and certainly the cobweb-ridden corners of our collective mind.

Last but not least is the fearless Guild School class of 1998, posed in front of the Gallery, that little gem a few doors up from the foot of Main St., where you’ll probably still find Paul Manning’s rig, and if you look a little further, you’ll find the man himself. Say hello from us.

After much conversation on this picture of the class,we all decided it had to be your class of 1998..Erin Carter was in your 1999 class and she isn’t in the picture Katie Marsh was in your ’98 class (Katie is in the yellow jacket)..I guess you taught the class both years.

Hi Cindy, I bow to the majority vote. I thought maybe we’d taught it twice in Castine, but have no records for the ’98 class, so thanks for setting the record straight. It was such a complex class, I’m amazed that many people took the plunge, but thanks, everyone, for going along with our craziness!

Thank you, Pat and Noel. Taking your potting shed class was one of the highlights of my time at The Guild School…loved reading about the specs on this class above. Miss you guys so much and was thrilled to see your work and read about it!

Thank you, Kaye, glad you enjoyed it.

I had to wait til I had enough time to read and appreciate this one. I love seeing the working drawings. You shipped old glass? And just when I think you can’t go any further in your craziness, you do. “And just for fun, a screen door.”

Thanks, Christi. Yes, we were nuts. Still are, but it doesn’t show as much.

P.S. I can’t wait for the book.